Can you leg press heavy weight but struggle with a clean lunge? Here’s why that matters after an MCL injury

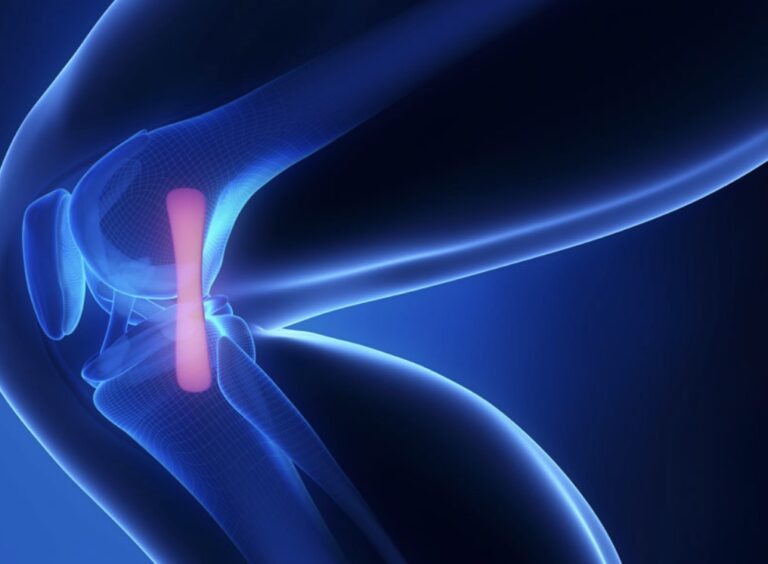

The Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL) is the band of tissue on the inside of your knee that prevents the joint from collapsing inward. It is commonly injured through sudden twisting, force applied from the outside of the knee, or during sports that require rapid changes in direction — such as football, basketball, or skiing. Most MCL injuries do not require surgery, but they do require a structured rehabilitation process — because the ligament needs controlled stress, strengthening, and gradual re-exposure to load in order to heal fully. The goal of rehab is not only to reduce pain, but to restore stability, strength, confidence, and readiness for real movement patterns again.

Why gradual re-conditioning matters

After an MCL injury, the knee doesn’t just need strength — it needs control. Heavy lifting on machines can sometimes hide weak links, because the machine locks your movement into a fixed path. When you ask the knee to control your whole body in space — like a strict bodyweight lunge — you suddenly discover what is really happening with stability, alignment, balance, and motor control. This is why someone might be moving heavy weight on a leg press, but still struggle with a strict lunge: they’ve built force output, but not movement quality. MCL rehab needs both — strength and control — and the only way to build real control is through gradual, progressive re-conditioning that starts with mastering your own bodyweight first.

Why 150% Bodyweight Single-Leg Leg Press is a Late-Stage MCL Recovery Goal

A single-leg leg press at around 150% of your body weight is a commonly used late-stage benchmark in MCL rehab. This level of loading develops the strength and confidence needed to return to sport — because it challenges the quadriceps, glutes, and stabilisers that protect the knee under high force.

Important: 150% bodyweight is a goal — not a starting point – That number is something to work towards, not to jump straight into.

Laying the foundation for this starts with bodyweight control: single-leg balance, single-leg squats, and especially lunges. These patterns teach the knee to track correctly, strengthen the supporting muscles, and build motor control before adding heavier external load.

If bodyweight lunges feel unstable, painful, or you cannot keep the knee aligned — that is direct feedback that your knee is not yet ready to load heavy.

Progression in MCL rehab should feel earned, gradual, and controlled.

Why this goal matters

• Strength + stability

Builds the strength your knee needs to handle the forces of real sport.

• Sport-specific readiness

This is a bridge to more dynamic movements like jumping, deceleration, and cutting.

• Confidence building

Hitting this number helps athletes trust their knee again.

Step-by-step progression

- Master single-leg stability

Balance on one leg for 30 seconds with no collapse or wobbling. - Build bodyweight control first

Exercises like single-leg sit-to-stand, step-downs, and bodyweight lunges. - Progress load gradually

Maybe 1× bodyweight first — then 1.25× — then finally 1.5× if technique is perfect. - Stop if you feel sharp pain

Muscle effort is normal. Joint pain is not. - Integrate complementary drills

Balance work, agility ladders, and controlled directional changes prepare you for return-to-play.

Where lunges fit in

Lunges are appropriate in later-stage rehab. But form is non-negotiable:

- front knee stays aligned over ankle

- torso square, no twisting or side loading

- start shallow, increase range gradually

Forward and reverse lunges are typically safer earlier on than lateral variations.

Final word

True knee strength is built in layers. Bodyweight stability → lunges → gradual resistance → late-stage heavy load. Don’t rush the process, avoid re-injury by going slow and own each stage for a safer, stronger return.